26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

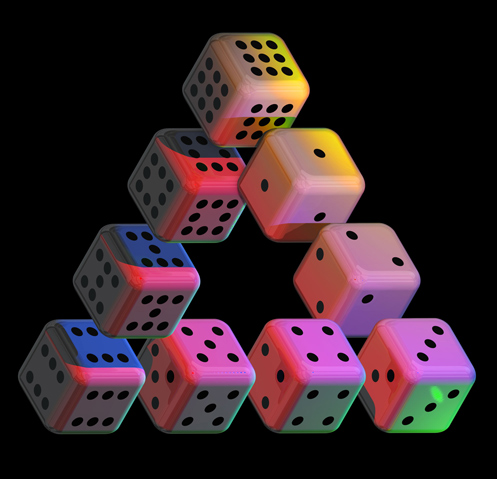

1 |

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

8 |

+ |

= |

|

4+3 |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

14 |

15 |

|

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

24 |

|

26 |

+ |

= |

|

1+1+5 |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

7 |

|

+ |

= |

|

8+3 |

= |

|

1+1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|

|

16 |

17 |

18 |

|

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

|

25 |

|

+ |

= |

|

2+3+6 |

= |

|

1+1 |

|

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

+ |

= |

|

3+5+1 |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

+ |

= |

|

1+2+6 |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

1+2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

1+5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

1+8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

2+1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

3 |

= |

|

2+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

= |

|

occurs |

x |

2 |

= |

|

1+8 |

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4+5 |

|

|

2+6 |

|

1+2+6 |

|

5+4 |

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

21 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

1 |

|

13 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

1 |

|

14 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

|

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

1 |

|

20 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

1 |

|

25 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

39 |

|

8 |

|

111 |

39 |

39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3+9 |

|

|

|

1+1+1 |

3+9 |

3+9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

8 |

|

|

12 |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+2 |

|

|

|

|

1+2 |

1+2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

8 |

|

|

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

1 |

|

20 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

21 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

1 |

|

13 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

1 |

|

14 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

1 |

|

25 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

|

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

39 |

|

8 |

|

111 |

39 |

39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3+9 |

|

|

|

1+1+1 |

3+9 |

3+9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

8 |

|

|

12 |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+2 |

|

|

|

|

1+2 |

1+2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

8 |

|

|

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE LETTERS AND NUMBERS BEGATS A SECOND READING

HOLY BIBLE

Scofield References

Page 1117 A.D. 30.

Jesus answered and said unto him, Verily, verily,

I say unto thee, Except a man be born again,

He cannot see the kingdom of God.

St John Chapter 3 verse 3

3 + 3 3 x 3

6 x 9

54

5 + 4

9

IN SEARCH OF THE MIRACULOUS

Fragments of an Unknown Teaching

P.D.Oupensky 1878- 1947

Page 217

" 'A man may be born, but in order to be born he must first die, and in order to die he must first awake.' "

" 'When a man awakes he can die; when he dies he can be born' "

Daily Mail, Wednesday, May 11, 2016

Page 51

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS

Compiled by Charles Legge

The trail of Christ's Grail

QUESTION What is the origin of

the Holy Grail story?

What is a 'grail'?

ACCORDING to Grail legend, the Holy Grail was the cup (or platter, cauldron or stone) from which Jesus drank at the Last Supper and which Joseph of Arimathea later used to collect drops of Jesus's blood at the crucifixion. Legend has it that Joseph then brought the cup to Britain, where it was lost. The Holy Grail then became part of Arthurian legend.

It was believed to be kept in a mysterious castle in a wasteland, guarded by a custodian called the Fisher King, who suffered from a wound that would not heal. His recovery and the renewal of the blighted lands depended on the successful completion of the quest to find the Grail. The magical properties attributed to the Holy Grail have been plausibly traced to the 'horn of plenty' of Celtic myth that satisfied the tastes and needs of all who ate and drank from it.

The Holy Grail first appeared in a written text in Chretien de Troyes's Old French verse romance, Perceval, le Conte du Graal from about 1180. De Troyes claimed he received knowledge of the tale from a book from his patron Philip, Count of Flanders.

His prologue specifically implies this was his source, ending 'it is the story of the Grail of which the count gave him the book'. But there is speculation as to whether this book existed: 12th-century writers were sensitive to the charge they invented stories for which they had no `authority'.

During the next half-century, several works, both in verse and prose, were written about the quest for the Grail although the story, and the principal character, vary from one work to another.

The word graal, as it was historically spelled, comes from Old French graal or great, cognate with Old Provençal grazal and Old Catalan gresal, meaning a cup or bowl of earthenware, wood or metal.

The most commonly accepted etymology derives it from Latin gradalis or gradale via an earlier form, cratalis, a derivative of crater or cratus, borrowed from the Greek krater, a large wine-mixing vessel. The Grail myth was revived in the lath century by romantic authors Scott and Tennyson, Pre-Raphaelite artists, and composers, notably Richard Wagner.

The story has persisted in novels by Charles Williams, C. S. Lewis, John Cowper Powys, in Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code and the Indiana Jones movies.

Eric Lowndes, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire.

THE

HOLY GRAIL

A

HOLY GIRL

IS

A |

|

1 |

|

1 |

A |

1 |

1 |

1 |

H |

|

8 |

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

G |

|

7 |

|

4 |

GIRL |

46 |

28 |

1 |

I |

|

9 |

|

2 |

IS |

28 |

10 |

1 |

|

|

25 |

|

11 |

Add to Reduce |

|

|

|

|

|

2+5 |

|

1+1 |

Reduce to Deduce |

1+3+5 |

6+3 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Essence of Number |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

GRAIL |

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

A |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

GIRL |

46 |

28 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

IS |

28 |

10 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

First Total |

|

|

|

|

|

4+2 |

|

2+3 |

Add to Reduce |

2+7+5 |

1+4+0 |

2+3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Second Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce to Deduce |

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Essence of Number |

|

|

|

H |

|

8 |

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

W |

|

5 |

|

6 |

WOMANS |

85 |

22 |

4 |

W |

|

5 |

|

4 |

WOMB |

53 |

17 |

8 |

|

|

18 |

|

14 |

First Total |

|

|

18 |

|

|

1+8 |

|

1+4 |

Add to Reduce |

1+9+8 |

6+3 |

1+8 |

|

|

|

|

|

Second Total |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce to Deduce |

1+8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Essence of Number |

|

|

|

A

HOLY WOMANS WOMB

IS

THE

HOLY GRAIL

A

HOLY GIRL

IS

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

GRAIL |

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

First Total |

|

|

|

|

|

4+2 |

|

1+2 |

Add to Reduce |

1+4+0 |

6+8 |

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Second Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce to Deduce |

|

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Essence of Number |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

20 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

1 |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

|

3 |

|

33 |

15 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

1 |

|

15 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

|

12 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

1 |

|

25 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

|

4 |

|

60 |

24 |

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

1 |

|

7 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

1 |

|

18 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

1 |

|

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

1 |

|

12 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

29 |

|

5 |

|

47 |

29 |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+4 |

1+6 |

1+8 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

GRAIL |

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

First Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+4 |

|

1+2 |

Add to Reduce |

1+4+0 |

6+8 |

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

Second Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce to Deduce |

|

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

Essence of Number |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

20 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

1 |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

1 |

|

15 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

|

12 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

1 |

|

25 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

1 |

|

7 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

1 |

|

18 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

1 |

|

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

1 |

|

12 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+4 |

1+6 |

1+8 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

GRAIL |

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

First Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+4 |

|

1+2 |

Add to Reduce |

1+4+0 |

6+8 |

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

Second Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce to Deduce |

|

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

Essence of Number |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

20 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

|

12 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

1 |

|

12 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

1 |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

1 |

|

15 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

1 |

|

25 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

1 |

|

7 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

1 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

1 |

|

18 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

1 |

|

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

33 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+4 |

1+6 |

1+8 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

HOLY |

60 |

24 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

GRAIL |

47 |

29 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

First Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+4 |

|

1+2 |

Add to Reduce |

1+4+0 |

6+8 |

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

Second Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce to Deduce |

|

1+4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

Essence of Number |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RE THE HOLY FAMILY

REMEMBER THE HOLY SEVEN

THE ROOT NUMBER OF THE 6 LETTERED JOSEPH = 1 (6+1) = 7

THE ROOT NUMBER OF THE 5 LETTERED JESUS = 2 (2+5) = 7

THE ROOT NUMBER OF THE 4 LETTERED MARY = 3 (4+3) = 7

J |

= |

1 |

- |

6 |

JOSEPH |

73 |

28 |

1 |

J |

= |

1 |

- |

5 |

JESUS |

74 |

11 |

2 |

M |

= |

4 |

- |

4 |

MARY |

57 |

21 |

3 |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

|

- |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

1+5 |

- |

2+0+4 |

6+0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

JOSEPH |

1 |

6+1 |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

JESUS |

2 |

5+2 |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

MARY |

3 |

4+3 |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

- |

- |

- |

-3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

O |

15 |

6 |

6 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P |

16 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

H |

8 |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

- |

J |

= |

1 |

- |

6 |

JOSEPH |

73 |

37 |

28 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

JESUS |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

U |

21 |

3 |

3 |

- |

- |

2 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

= |

1 |

- |

5 |

JESUS |

74 |

29 |

11 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

MARY |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

M |

13 |

4 |

4 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R |

18 |

9 |

9 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y |

25 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

M |

= |

4 |

- |

4 |

MARY |

57 |

21 |

21 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

15 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1+5 |

- |

2+0+4 |

8+7 |

6+0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1+0 |

- |

1+4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

6 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1+5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

|

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JOSEPH JESUS MARY

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

- |

- |

- |

-3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

O |

15 |

6 |

6 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P |

16 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

H |

8 |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

U |

21 |

3 |

3 |

- |

- |

2 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

M |

13 |

4 |

4 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R |

18 |

9 |

9 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y |

25 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

15 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1+5 |

- |

2+0+4 |

8+7 |

6+0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1+0 |

- |

1+4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

6 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1+5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

|

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

- |

- |

- |

-3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

U |

21 |

3 |

3 |

- |

- |

2 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

M |

13 |

4 |

4 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

O |

15 |

6 |

6 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P |

16 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y |

25 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

H |

8 |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R |

18 |

9 |

9 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

- |

- |

6 |

|

15 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1+5 |

- |

2+0+4 |

8+7 |

6+0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1+0 |

- |

1+4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

6 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1+5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

|

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

- |

- |

- |

-3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

J |

10 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S |

19 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

U |

21 |

3 |

3 |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

M |

13 |

4 |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

O |

15 |

6 |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P |

16 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y |

25 |

7 |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

H |

8 |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R |

18 |

9 |

9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

- |

- |

6 |

|

15 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1+5 |

- |

2+0+4 |

8+7 |

6+0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1+0 |

- |

1+4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

6 |

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1+5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

|

JOSEPH JESUS MARY |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

J |

= |

1 |

6 |

JOSEPH |

73 |

37 |

1 |

J |

= |

1 |

5 |

JESUS |

74 |

29 |

2 |

M |

= |

4 |

4 |

MARY |

57 |

21 |

3 |

6 |

JOSEPH |

73 |

37 |

1 |

11 |

JESUS CHRIST |

151 |

70 |

7 |

4 |

MARY |

57 |

21 |

3 |

|

- |

|

|

|

1+1 |

- |

2+8+1 |

1+2+8 |

1+1 |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

- |

1+1 |

1+1 |

- |

|

- |

|

|

|

J |

= |

1 |

- |

6 |

JOSEPH |

73 |

28 |

1 |

C |

= |

3 |

- |

6 |

CHRIST |

77 |

41 |

5 |

M |

= |

4 |

- |

4 |

MARY |

57 |

21 |

3 |

- |

- |

8 |

- |

|

- |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

1+6 |

- |

2+0+7 |

9+0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

J |

= |

1 |

- |

6 |

JOSEPH |

73 |

28 |

1 |

J |

= |

1 |

- |

5 |

JESUS |

74 |

11 |

2 |

M |

= |

4 |

- |

4 |

MARY |

57 |

21 |

3 |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

|

- |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

1+5 |

- |

2+0+4 |

6+0 |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

JOSEPH |

1 |

6+1 |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

JESUS |

2 |

5+2 |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

MARY |

3 |

4+3 |

7 |

SEVENS EVENS SEVEN

- |

EGYPT |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

E |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

- |

5 |

1 |

G |

7 |

7 |

7 |

- |

7 |

- |

1 |

Y |

25 |

7 |

7 |

- |

7 |

- |

1 |

P |

16 |

7 |

7 |

- |

7 |

- |

1 |

T |

20 |

2 |

2 |

|

- |

2 |

5 |

EGYPT |

73 |

28 |

28 |

- |

21 |

7 |

|

- |

7+3 |

2+8 |

2+8 |

- |

2+1 |

- |

5 |

EGYPT |

10 |

10 |

10 |

|

3 |

7 |

|

- |

1+0 |

1+0 |

1+0 |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

EGYPT |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

3 |

7 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oedipus

Oedipus was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father ...

Oedipus complex · Oedipus Rex · ?Oedipus (Euripides) · Oedipus at Colonus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oedipus_Rex

Oedipus Rex, also known by its Greek title, Oedipus Tyrannus or Oedipus the King, is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC.

Written by: Sophocles

Series: Theban Plays

Original language: ?Classical Greek

Date premiered?: c. 429 BC

Oedipus - Wikipedia

Oedipus definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/oedipus

Oedipus definition: the son of Laius and Jocasta , the king and queen of Thebes , who killed his father ,...

Oedipus was the son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of Thebes. ... Little Oedipus/Oidipous was named after the swelling from the injuries to his feet and ankles ("swollen foot"). The word "oedema" (British English) or "edema" (American English) is from this same Greek word for swelling: ??d?µa, or oedema.

Oedipus complex definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/oedipus-complex

Oedipus complex definition: If a boy or man has an Oedipus complex , he feels sexual desire for his mother and has... | Meaning, pronunciation, translations and ...

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/oedipus-complex

Oedipus complex definition: in psychology (= the study of the human mind), a child's sexual desire for their parent of the opposite sex, especially that of a boy for ...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

|

9 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

1+6 |

|

|

= |

|

- |

-`` |

15 |

|

|

9 |

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

4+3 |

|

|

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

5 |

4 |

|

7 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

1+9 |

|

|

1+0 |

|

- |

- |

|

5 |

4 |

|

16 |

21 |

|

|

|

|

4+6 |

|

|

1+0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

15 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

16 |

21 |

19 |

|

|

|

8+9 |

|

|

1+7 |

|

- |

- |

6 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

= |

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

4 |

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

7 |

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

occurs |

x |

|

= |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+0 |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

|

9 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

1+6 |

|

|

= |

|

- |

-`` |

15 |

|

|

9 |

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

4+3 |

|

|

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

5 |

4 |

|

7 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

1+9 |

|

|

1+0 |

|

- |

- |

|

5 |

4 |

|

16 |

21 |

|

|

|

|

4+6 |

|

|

1+0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

15 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

16 |

21 |

19 |

|

|

|

8+9 |

|

|

1+7 |

|

- |

- |

6 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

= |

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

4 |

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

occurs |

x |

|

= |

7 |

|

|

- |

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

occurs |

x |

|

= |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+0 |

- |

6 |

5 |

4 |

9 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O |

|

6 |

|

1 |

O |

15 |

6 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

|

|

|

1 |

E |

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D |

|

|

|

1 |

D |

4 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

1 |

I |

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

16 |

7 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

3 |

|

1 |

U |

21 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

|

|

|

1 |

S |

19 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

89 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

|

8+9 |

4+4 |

3+5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

|

|

|

1 |

S |

19 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

3 |

|

1 |

U |

21 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D |

|

|

|

1 |

D |

4 |

4 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

E |

|

|

|

1 |

E |

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O |

|

6 |

|

1 |

O |

15 |

6 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

16 |

7 |

7 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

I |

|

|

|

1 |

I |

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

89 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

|

8+9 |

4+4 |

3+5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

|

|

|

1 |

S |

19 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U |

|

3 |

|

1 |

U |

21 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D |

|

|

|

1 |

D |

4 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

|

|

|

1 |

E |

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O |

|

6 |

|

1 |

O |

15 |

6 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

16 |

7 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

|

|

|

1 |

I |

9 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

89 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3+5 |

|

|

|

8+9 |

4+4 |

3+5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1+7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

- |

- |

|

|

M+N+E+M |

45 |

18 |

|

|

O |

15 |

6 |

|

|

S+Y+N+E |

63 |

18 |

|

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

123 |

42 |

33 |

- |

|

1+2+3 |

4+2 |

3+3 |

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

6 |

6 |

6 |

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

- |

- |

|

|

M+N |

27 |

9 |

|

|

E+M |

18 |

9 |

|

|

O |

15 |

6 |

|

|

S+Y+N+E |

63 |

18 |

|

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

123 |

42 |

33 |

- |

|

1+2+3 |

4+2 |

3+3 |

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

6 |

6 |

6 |

Mnemosyne, in Greek mythology, the goddess of memory. A Titaness, she was the daughter of Uranus (Heaven) and Gaea (Earth), and, according to Hesiod, the mother (by Zeus) of the nine Muses. She gave birth to the Muses after Zeus went to Pieria and stayed with her nine consecutive nights.

Mnemosyne - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mnemosyne

Mythology - A Titanide, or Titaness, Mnemosyne was the daughter of the Titans Uranus and Gaia. Mnemosyne was the mother of the nine Muses, fathered by her nephew, Zeus: Calliope (epic poetry) Clio (history)

Parents?: ?Uranus? and ?Gaia

Consorts?: Zeus

Roman equivalent Moneta

Offspring?: ?The Muses?: Calliope?; Clio?; Erato?; Eu...

Mnemosyne (/n?'m?z?ni, n?'m?s?ni/; Greek: pronounced [mn??mosý?n??]) is the goddess of memory in Greek mythology. "Mnemosyne" is derived from the same source as the word mnemonic, that being the Greek word mneme, which means "remembrance, memory".[1][

In Hesiod’s Theogony, kings and poets receive their powers of authoritative speech from their possession of Mnemosyne and their special relationship with the Muses.

Zeus and Mnemosyne slept together for nine consecutive nights, thus conceiving the nine Muses. Mnemosyne also presided over a pool[2] in Hades, counterpart to the river Lethe, according to a series of 4th century BC Greek funerary inscriptions in dactylic hexameter. Dead souls drank from Lethe so they would not remember their past lives when reincarnated. In Orphism, the initiated were taught to instead drink from the Mnemosyne, the river of memory, which would stop the transmigration of the soul.[3]

Appearance in oral literature[edit]

Jupiter, disguised as a shepherd, tempts Mnemosyne, goddess of memory by Jacob de Wit (1727)

Although she was categorized as one of the Titans in the Theogony, Mnemosyne didn’t quite fit that distinction.[4] Titans were hardly worshiped in Ancient Greece, and were thought of as so archaic as to belong to the ancient past.[4] They resembled historical figures more than anything else. Mnemosyne, on the other hand, traditionally appeared in the first few lines of many oral epic poems?[5]—she appears in both the Iliad and the Odyssey, among others—as the speaker called upon her aid in accurately remembering and performing the poem he was about to recite. Mnemosyne is thought to have been given the distinction of “Titan” because memory was so important and basic to the oral culture of the Greeks that they deemed her one of the essential building blocks of civilization in their creation myth.[5]

Later, once written literature overtook the oral recitation of epics, Plato made reference in his Euthydemus to the older tradition of invoking Mnemosyne. The character Socrates prepares to recount a story and says “?st? ????e, ?a??pe? ?? (275d) p???ta?, d??µa? ????µe??? t?? d????se?? ???sa? te ?a? ???µ?s???? ?p??a?e?s?a?.” which translates to “Consequently, like the poets, I must needs begin my narrative with an invocation of the Muses and Memory” (emphasis added).[6] Aristophanes also harked back to the tradition in his play Lysistrata when a drunken Spartan ambassador invokes her name while prancing around pretending to be a bard from times of yore.[7]

Cult of Asclepius[edit]

Mnemosyne was one of the deities worshiped in the cult of Asclepius that formed in Ancient Greece around the 5th century BC.[8] Asclepius, a Greek hero and god of medicine, was said to have been able to cure maladies, and the cult incorporated a multitude of other Greek heroes and gods in its process of healing.[8] The exact order of the offerings and prayers varied by location,[9] and the supplicant often made an offering to Mnemosyne.[8] After making an offering to Asclepius himself, in some locations, one last prayer was said to Mnemosyne as the supplicant moved to the holiest portion of the asclepeion to incubate.[8] The hope was that a prayer to Mnemosyne would help the supplicant remember any visions had while sleeping there.[9]

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

- |

- |

|

|

M+N+E+M |

45 |

18 |

|

|

O |

15 |

6 |

|

|

S+Y+N+E |

63 |

18 |

|

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

123 |

42 |

33 |

- |

|

1+2+3 |

4+2 |

3+3 |

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

6 |

6 |

6 |

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

- |

- |

|

|

M+N |

27 |

9 |

|

|

E+M |

18 |

9 |

|

|

O |

15 |

6 |

|

|

S+Y+N+E |

63 |

18 |

|

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

123 |

42 |

33 |

- |

|

1+2+3 |

4+2 |

3+3 |

9 |

MNEMOSYNE |

6 |

6 |

6 |

Mnemosyne : Greek Goddess of Memory and Mother of the Muses

www.goddessgift.com/goddess-myths/g-mnemosyne.htm

Mnemosyne, Greek goddess of memory, was considered one of the most powerful goddesses of her time. After all, it is memory, some believe, that is a gift that ...

The word "mnemonic" is derived from the Ancient Greek word (mnemonikos), meaning "of memory, or relating to memory" and is related to Mnemosyne ("rem